In my last blog post “Virtual currencies deciphered (1): the new legal definition and AMLD5” I discussed the new legal definition for virtual currencies (hereinafter abbreviated as “VC or VCs”) according to 5AMLD. When, as part of the evolution money, a fundamentally new type of money is created, a clear definitional distinction to the “old” types of money, such as cash, bank money and e-money, is needed as part of the legal regulation. There appears to be a risk of confusion between VCs and e-money, according to the warning in Recital 10 of the new 5AMLD. If the legal definition of an EU directive does not provide for a clear distinction, this causes a problem for supervisory authorities. The worst case scenario is that this creates inharmony at the EU level.

Demand deposits versus e-money

The situation today regarding the distinction between bank money (demand deposits) and account-based e-money issued by credit institutions is as follows: Prepaid credit cards equipped with the brands of international card systems (such as Mastercard or Visa) are classified differently for regulatory purposes. Despite clear guidelines from supervisory authorities and the ECB’s statistical definition criteria, some credit institutions (e.g. in Germany) classify these non-interest-bearing balances as demand deposits and others as e-money. This confusion has consequences not only for the statistical “undervaluation” of e-money in the ECB’s statistics, but also for the holder of such prepaid credit cards with regard to deposit protection.

The question of whether these products should systematically even be classed as electronic money is justified. It does not have the characteristic of a closed e-money account cycle, which is typical for e-money. In contrast to “real” e-money accounts (such as PayPal), prepaid credit cards do not offer the option of transferring the value units from one e-money account to another within the e-money system. In some countries, the balance can be used directly in interbank payment transactions. In Italy, where the prepaid account of many prepaid credit cards is assigned to an IBAN (so-called IBAN prepaid cards), the product is still classified as e-money.

The unclear regulatory classification has therefore further consequences. For example, supervisors face the difficult question of whether and, if so, what criteria must be met for an e-money account to constitute a payment account under the Payment Accounts Directive.

The genuine e-money was a VC

The cause of these problems is the regulatory sin that since EMD2 (2009) at the latest, account-based e-money has also been classified as e-money in accordance with the legal definition. The genuine e-money that was celebrated in the second half of the 1990s as a new stage of the money evolution was not account-based, but a “token” and thus a bearer instrument. It was a non-reproducible data set consisting of bits and bytes stored on a chip (card or PC).

Those of us who have been around the block a few times can still remember the, unfortunately too early pioneers, Mondex and E-Cash. However, evolution eats its children. In the European market, most electronic wallets in the form of “genuine” e-money only managed to survive for a maximum of two decades. The GeldKarte, which still exists in Germany, is also a relic from this period. As digital cash (bearer instrument), this early form of e-money was a real leap forward in money evolution and, in terms of decentralisation, a precursor of today’s VC. Compared to the old types of money, i.e. cash and bank money, this new type of money naturally had no problems of differentiation.

The problems only arose due to the fact that a not unusual mutation of bank money, which developed outside the regulated banking sector (demand deposits), was also classified as a new type of money and thus placed into the wrong (but from a regulatory perspective nearly empty) e-money pot. In hindsight, not a good idea. There are no systemic differences between bank demand deposits and e-money accounts. All elements of the legal definition of e-money (according to EMD2) also apply to my current account at the bank. National supervisory authorities use functional differentiation criteria that are not harmonised at EU level.

Nomen est omen

With VC, we now again have a new type of money from a legal point of view and are therefore faced again with the question of differentiation, in particular with regard to e-money. Regulators have named the new type of money “virtual currency”. Not a particularly good choice. In contrast to “lawless” money, when choosing the term “currency” we enter a territory governed by the state and law. According to German Wikipedia, a currency is “in the broader sense, the constitution and order of a state’s entire monetary system”.

However, the vagabonding VCs are so far very separate from any order, law and state. The term reveals at most a subconscious wishful thinking of the godparents to somehow domesticate the new creature. Can the adjective “virtual” in the sense of “not real, not existing in reality but seemingly real, the opposite of completely real” perhaps help us further? Maybe so. For this, we must first look at the still prevailing doctrine of state money: The money is to be issued under a state-controlled monopoly (central bank).

Since the rise of bank money, which is mainly used by banks, or even sooner, the doctrine has been that money has to be issued by a central bank. Control is ensured by the systemic dependency of privately issued bank money on the state monopoly money of the central bank (cash and CB bank money). Private bank money is also issued in the state currency unit, has exactly the same exchange rate and should always be exchangeable into state monopoly money during “normal” times (i.e. when there is no run on banks). Our monetary order is therefore based on the money issued by the central bank (economists use the terms “outsight money” or “base money” here). In our doctrine, this money is the “genuine” real money guaranteed by the state (although it remains unclear what the guarantee is).

Due to the inevitable link between the banks’ private bank money and the base money of the central bank, this money receives a sort-of quality seal and is therefore also perceived to be “real” money, equivalent in quality to the base money. From this “indoctrinated” perspective, the adjective “virtual” makes sense: it is not “real” money in the sense that it is issued or controlled by the state.

Is e-money also virtual?

And what about e-money? Is it real money or is it also just virtual? In the mid-1990s, due to the emergence of e-money, central banks had similar fears of losing control as they have today regarding VCs. Back then, there were also fears – and rightly so – about vagabonding private “currencies” existing in parallel to the state currency. And it nearly did all go wrong. At the last minute, the ECB was able (with a lot of political pressure) to instigate the decisive amendment of the first e-Money Directive (2000/46/EC): The obligation of the issuer to redeem the e-money in cash or bank money at par value (Art. 3).

With that, the new e-money was inevitably linked to the basic state money. Interestingly, the rescue of the existing monetary order was disguised as a consumer-friendly measure “to ensure bearer confidence” (Recital 9). Since then, electronic money has been considered part of the “real” money.

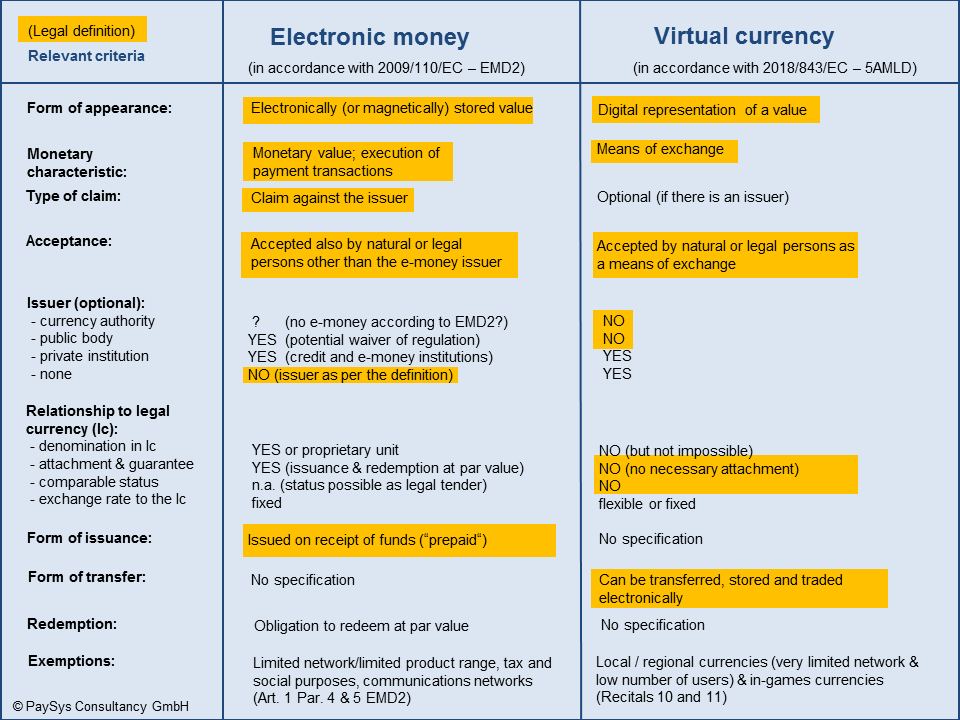

e-money versus VC

This brings us to the first important difference between e-money and VC. In contrast to e-money, a VC is “is not necessarily attached to a legally established currency” (legal definition, Art. 3 No. 18 of 5AMLD). The link between e-money and base money is ensured by a legal requirement and is therefore not a prerequisite for its definition. The “necessary attachment” for both bank money and e-money is only guaranteed by the issuer’s obligation to redeem at par value (in the first case in cash, in the second case in cash or bank money).

It would now be possible to legally oblige the VC issuer (if there is one) – as with e-money – to attach the VC to a legally established currency. By definition, e-money always has an identifiable issuer. A VC may, but it does not have to, be circulated by an issuer (e.g. Bitcoin, which does not have an issuer). Would an issuer-linked VC mutate into e-money if there was a legal requirement to redeem it at par value? And what does “at par value” mean if the value is in Mickey Mouse units? In this case, the exchange can only take place at the current exchange rate. This means that there is no “necessary attachment”, which is one of the main characteristics as per the definition. The non-existent forced attachment is not part of the DNA of a VC, but is only the result of the (remaining) lack of domestication. It confirms the assumption that the legal definition of VC was designed as a catch-all provision.

Another distinguishing feature of e-money compared to a VC is the issue of payment of a sum of money. The essential condition for e-money is that it is prepaid. No e-money without prepayment. As a general rule, this results in a claim against the issuer. (So far, it is possible to theoretically imagine the interesting constellation of “prepaid, but without a claim against the issuer”, which would mean that there would be no e-money as per the legal definition.) In its first Report on Virtual Currency Schemes (2012), the ECB had caused some conceptual confusion, not only because it used the legal definition of e-money as contained in the first e-Money Directive, which had already long been dismissed, but also because it erroneously declared prepaid products with a claim character to be VCs.

Another criterion for e-money is the three-sided acceptance relationship. As per the definition, it only constitutes e-money if the holder can use the value units as a means of payment with a natural or legal person other than the issuer. This condition is missing in the definition of VCs. Accordingly, digital value units that are issued by an issuer (prepaid or not) and that can only be used as a means of exchange with that issuer, by definition fall into the category of VC.

Therefore, digital value units that can only be used in the context of an ICO (Initial Coin Offering) for future planned products or services of the entrepreneur who is still seeking capital fall into the category of VC. This appears to be the intention. However, will, for example, today’s voucher cards or other e-vouchers with a two-sided acceptance relationship (expressly no e-money) suddenly also turn into VCs? The unintended consequences would be disastrous: KYC for closed-loop gift cards. This is also not mitigated by the exemption which is available for VCs and which is much narrower than that available to e-money. This point needs to be clarified by the national legislator as part of the implementation of 5AMLD.

Titelbild / Cover picture: Copyright © fotolia