Update on the European Payments Initiative (EPI) and the EU Retail Payments Strategy (RPS)

In the first part of this blog post on the European Payments Initiative (EPI), we analysed the first press release from the 16 banks involved (dated 2 July 2020) and the simultaneously published congratulatory statements from its parents (ECB and EU Commission). Shortly before this (26 June), the European Commission had terminated a public “Consultation on a retail payment strategy for the EU”. In the meantime, on 24 September, the Retail Payments Strategy (RPS) was published, and as stated by the Commission (p.26), fully considers the varied input received during the consultation process from a total of 189 stakeholders (consumers, merchants, associations, banks, central banks, supervisory authorities, scientists, NGOs, PSPs etc.). The content of the paper is worth reading and provides enough material for numerous blog posts.

Table of Contents

In this post, I would now like to take a closer look at the first pillar for strategic action:

“Increasingly digital and instant payment solutions with pan-European reach” (pp. 5-15)

as comprehensive regulatory support and promotional program for the banks’ EPI. After all, the newly born EPI needs to be provided with enough milk from its parents.

Formally, the RPS appears to be system-neutral. It supports a whole range of solutions that are home-grown, i.e. have their roots in Europe, have a pan-European reach, are based on real-time payments and are capable of competing with global (non-European) payers (particularly Mastercard and Visa). For this reason, it only dedicates two sentences to EPI and does not contain the information that the EPI is mainly the result of regulatory pressure exerted by the ECB and the Commission. In addition to the EPI, the P27 as well as the European Mobile Payment Systems Association (EMPSA) are named as further promising initiatives.

P27 may or may not be a good example from the RPS’s perspective. P27 is an initiative that was started in 2017 by six large Scandinavian banks to establish a new infrastructure or platform for domestic and cross-border transactions (instant & batch) within Denmark, Sweden and Finland for a total of 27 million people (hence the name). The start is planned for 2021. This does not yet sound properly pan-European (over 500 million inhabitants). But what will weigh even more heavily on people’s hearts, is the fact that P27 has decided to get together with the enemy that is Mastercard. This non-European global player is even tasked with operating the new platform.

Where are the global big players dominant?

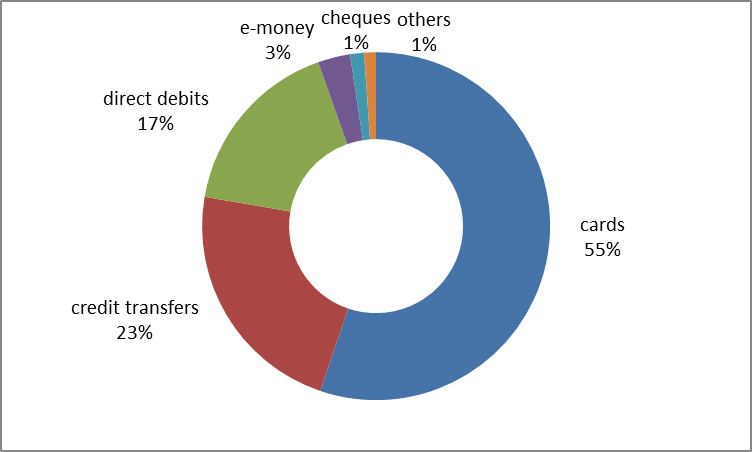

Why do we as Europeans have to defend ourselves against these “big global players”? In what markets and at what level are non-European providers dominant? In European payment transactions, a differentiation is normally made between the following payment methods (market shares in 2019 on a transaction basis):

(Source ECB statistics)

Credit transfers, direct debits and cheques are firmly in the hands of European banks, at the level of payment services providers (PSPs) as well as schemes (SEPA schemes). With regard to e-money, PayPal (as a scheme and PSP) and prepaid credit cards (American schemes but European PSPs) are dominant. In this segment, we indeed see a dominance of the global player PayPal (ca. 70% market share based on turnover).

With respect to card business, we see a multitude of different schemes in the EU27 (without the UK): seven large domestic card schemes (scheme and PSPs are European) and three American schemes (Mastercard, Visa and Amex). For Mastercard and Visa, only the schemes are non-European but not the licensed PSPs. Therefore, at scheme-level, we have 10 competing schemes, of which the seven European schemes have pretty much exactly a 50% market share (based on card turnover in 2018). However, more than 95% of card payments are made with cards issued by European PSPs.

This therefore begs the question why an alleged dominance would only be problematic at scheme-level but not at PSP-level. The second question is whether the word “dominance” is really justified based on a 50% market share. With respect to proper dominance, a differentiation must be made between domestic and cross-border card payments. As the cards of the European schemes can only be used cross-border within the EU based on the American brands (co-badging), at least at the physical POS, we probably have a nearly 100% dominance of the American schemes in this segment. In the card-not-present area (e-commerce), this dominance is likely to be smaller as many large e-commerce merchants in Europe increasingly accept the brands of the respective European schemes, depending on the demand in the respective member states.

The problem of the dominance of the American schemes decreases if in the segment of cross-border payments not only card payments but also credit transfers and direct debits are included as well.[1]

At least 75% of cross-border payments initiated by payers in the Eurozone are card transactions. The remaining 25% can be split into credit transfers and direct debits (source: ECB statistics 2019). However, based on turnover, the percentage of card payments only amounts to 0.7%.

The Commission’s statement that a handful of large global players dominate the entire intra-European cross-border payments market (p.3) is therefore not correct. The same applies to its conclusion that

“with the exception of those large players, including worldwide payment card networks and large technology providers, there is virtually no digital payment solution that can be used across Europe to make payments in shops and in e-commerce”,

unless a credit transfer did not count as “digital payment”. Unfortunately, there is no definition of the term “digital payment” which is often used in the RPS.

As we saw earlier, it does indeed make sense – also with regard to increasing competition – to differentiate between different levels in payment transactions:

- payment instrument (credit transfer, direct debit, card, etc.)

- payment process or scheme, incl. the respective technical infrastructure (SCT, SDD, PayPal, Mastercard, Visa, etc.)

- payment product (e.g. Visa card of Bank or B)

Due to the large number of schemes, there is strong competition in the card business, at scheme level (e.g. Mastercard vs. Visa) as well as at product level (e.g. Visa card or Bank A vs. Visa card of Bank B). However, it is a different story when looking at credit transfers. Here, you can find homogenous products that are all based on the SCT system. In terms of the product, an SCT credit transfer of Bank A is mostly identical with an SCT credit transfer of Bank B. With such homogenous products, the only competition that remains is regarding the price.

A real-time payment, where the payee can dispose of the amount received within a few seconds after the payment transaction has been concluded, could also be implemented for the usual payment instruments that are credit transfer, direct debit, cards and e-money. Some e-money payments such as PayPal are already executed as real-time payments. At scheme level, we can also envisage further instant payment schemes for credit transfers other than the SCT Inst which already exists.

What does the Commission’s new Instant Payment Strategy aim at?

With regard to instant payments, the RPS paper only focuses on credit transfers as payment instruments. At scheme level, the paper uses the plural form in one paragraph (“such solutions should largely rely on instant payment systems” – p. 5), but the rest of the paper only refers to the SCT Inst scheme, which was developed by the European Payment Council. Participation in SCT Inst is still voluntary and it is not yet a sure-fire success: 56% of European PSPs currently participate (as of 9 Oct. 2020)[2]. Looking at the map of member states, there are still a few gaps. If this does not improve quickly, EU regulation will force most PSPs to participate by the end of 2021 (p. 6). This would be an interesting case of European sector politics in favour of a private payment system of banks. One heretical idea that is the stuff of nightmares: It would also be possible to force merchants of a certain size to accept instant payments via PayPal. However, before this can happen, the European banks would need to obtain the majority of shares in PayPal. This would also bring about the intended result but in a simpler manner. Alright, alright… I know, this is completely far-fetched.

By the way, it is really remarkable that the mandatory participation in the SCT Inst scheme as proposed by the Commission was termed an “irrelevant” measure in the consultation (question 12) by the European Payment Council (EPC) as scheme owner, as well as by numerous banking associations (European Association of Co-operative Banks (EACB), European Savings and Retail Banking Group (ESBG), European Association of Public Banks and Funding Agencies (EAPBls) and also the Deutschen Kreditwirtschaft (DK)).[3] As for the reasons for this, the EPC states:

“Explicit market demand must be the driver for the creation of new payment schemes. The broad take-up of a SEPA-wide scheme depends on whether its features and processes as well as the underlying standards and technical specifications, add value for payment end-users and PSPs.”

Another quote:

“The EPC believes that a critical mass of scheme participants and reachable payment accounts will be achieved in due course through a natural, market-based process based on the benefits of the SCT Inst scheme for end-users and PSPs, however recognising the significant investment and operational changes required at PSP level.”

Is “Instant Payment” a sure-fire success?

The RPS identifies more show stoppers of the niche-product that are real-time credit transfers via SCT Inst on its way to the “new normal” that need to be addressed and solved as quickly as possible. Real-time credit transfers still present challenges for combating money laundering, terrorism financing and cyber-attacks. Money changes hands within seconds. In all likelihood, e-commerce payers won’t like the fact that any amounts paid via real-time credit transfers cannot be recalled. This is why RPS demands a charge-back option for real-time credit transfers so that the product can compete with card payments.

A further obstacle are unequal bank fees for the normal (D+1) and the credit transfer within seconds. For consumers, this goes without saying. Super-fast transactions require additional fees, as is the case for the Bahn, mail, Amazon, etc. Those who benefit from real-time payments are willing to pay the extra fees. However, such cost-benefit considerations are extremely dangerous for this still-niche product. Either, most payment users have been waiting impatiently for the high-flying product and are therefore willing to pay for the faster service or the product’s use is limited to certain payments in certain situations (the infamous friends with whom the restaurant bill is split). The Commission is pretty pessimistic (or realistic?) and fears that the latter will be the case. The consequence:

“Instant payments would remain a niche product, alongside regular credit transfers.” (p. 8).

This would put an end to the dream of this being the “new normal”. By way of regulatory interference, the Commission envisages a pricing regulation prohibiting differences in price between traditional and real-time credit transfers. Does this mean that there will soon be credit transfers with and without charge-back for the same price?

Does an alleged “sure-fire success” product really require heavy armour such as mandatory participation and price levelling? Is this sector politics which favours a specific payment system that is intended to compete with other systems in line with European competition laws? The Commission sees this impending danger and states that any political support will, of course, be carried out

“in full compliance with EU competition rules” (p. 9).

If the Commission had its way, real-time credit transfers on the basis of SCT Inst would become the miracle cure against the “dominance” of global card schemes and be used for purchases at physical and virtual POS. Unfortunately, it remains entirely unclear in the RPS paper what strategical fate is envisaged for the European card schemes. Early write-offs as collateral damage?

Pan-European payment solutions

The RPS paper loves the term “payment solutions”, phrased in the plural form. Does this refer to the type, scheme or product? Often it can only be deduced from the context what vertical level the reader is at. If an instrument (credit transfer) and scheme (SCT Inst) has already been determined, “solutions” can only refer to the product. Just as with a traditional credit transfer, I somehow still lack the required imagination how a heterogenous product can be developed from an SCT Inst credit transfer. Whether I initiate a real-time credit transfer at the POS from the wallet of Bank A or Bank B, it is the same (homogenous) product in both cases.

In other parts it probably was not intended for “solution” to mean “product”. That way, the Commission intends to keep playing an active political role

“to foster the development of competitive pan-European payment solutions that rely extensively on instant payments” (p. 9).

In this case, the term “solution” could also point to the payment instrument card or direct debit.

By the way, the EPI is also not very precise when it comes to the term “solution”. In the press release of 2 July, EPI is presented as “a new payment scheme and solution”. Very obviously, a solution is not a scheme. The EPI goal is stated to be a “unified pan-European payment solution” on the basis of the scheme “SCT Inst”. At the same time, it is not the intention to create a new scheme. This contradiction can only be solved if the new scheme is based on an existing scheme (SCT Inst), as e.g. a new card scheme that operates its clearing and settlement via SCT Inst.

It therefore also remains unclear what the Commission is aiming at with its statements on developing a label or logo:

“developing a ‘label’, accompanied by a visible logo, for eligible pan-European solutions” (p. 9).

A label / logo is generally used in payment transactions as a brand of acceptance for a scheme (e.g. Mastercard, Visa) and possibly also for a payment instrument where instrument and scheme are the same (PayPal, Sofort, etc.). Most likely, the Commission is not referring to a brand of acceptance of a scheme. With regard to SCT Inst, this would be a task for the EPC as scheme owner. One possibility would be a type of quality label along similar to “made in Europe”.

Stakeholder consultation

In this last part, I would briefly like to consider the public stakeholder consultation which preceded this strategy paper. One possible complaint could be that this consultation was mainly about a suitable way (strategy) to reach the goal, whereas the goal was already set. By the way: Who set this goal? Some further criticism is due regarding the way the consultation and the questions were drafted as the questions were preceded by blocks of text, the content of which influences participants while they are filling in the questionnaire. Be that as it may, the published results[4] of the consultation are interesting, particularly when clustering the answers according to participating groups of interested parties.

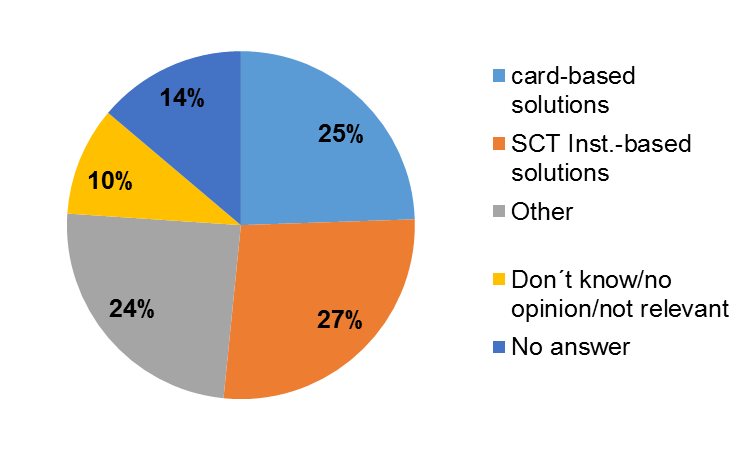

Finally, I would like to highlight one of the questions contained in the consultation. The answers to the question (no. 16) what cashless payment instrument would be the most beneficial solution for a European merchant:

Many of the participants who selected “other”, say that both payment instruments (card and real-time credit transfer) could be beneficial for merchants. They stated that this depended on a multitude of factors and a general answer was not possible. Therefore, in the view of the participants, the battle at the POS has definitely not been decided yet.

Do we even need a regulators’ strategy for “retail payments”? Will this strategy perhaps lead to less competition? Why is it not left up to the market or the competition?

[1] E-money should also be included here. However, there are no reliable figures available on the use of e-money in cross-border payments. The main player PayPal marks most transactions as “domestic” since payer and payee both have a PayPal account in Luxembourg.

[2] https://www.europeanpaymentscouncil.eu/what-we-do/sepa-instant-credit-transfer

[3] https://ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/finance-2020-retail-payments-strategy_en

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/finance-2020-retail-payments-strategy_en

Cover picture: Copyright © Adobe Stock / Dr. Hugo Godschalk