E-money is booming, at least in Europe. Never before have the central banks counted as many e-money transactions as in 2017. In some member states the competent authorities are inundated with registration applications from e-money institutions (EMIs). Now that registrations in the UK are no longer as attractive (but despite Brexit, around 40% of European EMIs are still registered there), Lithuania has become the new Mecca for e-money. In 2018, 20 new EMIs were registered there. In total, the Lithuanian EMI register comprises 49 institutions, almost all of them equipped with a European passport (except for six “small” EMIs, which are only allowed to be active in Lithuania). Apparently, Google was also unable to resist the enticing call of the Lithuanian central bank to come to “FinTech Paradise” and in December 2018 it was granted a licence to issue e-money. This article will provide some details on how e-money is developing in Europe and why quick e-money is currently trending.

Table of Contents

Victory march & grave digger

Does this mean that after 20 years, e-money can finally start its victory march in Europe?

In the summer of 1998, the European Commission made a first attempt to regulate this new creature. When the first e-Money Directive (2000/46/EC) was adopted in September 2000, no one had any idea what this baby would look like years later. The godparents wanted a card (or another data carrier) with a chip in which the digital value units would be stored. This digital cash was intended to drive away analogue cash. At that time, the baptism certificate read (phrased in a somewhat complicated manner):

For the purposes of this Directive, electronic money can be considered an electronic surrogate for coins and banknotes, which is stored on an electronic device such as a chip card or computer memory and which is generally intended for the purpose of effecting electronic payments of limited amounts. (Recital 3)

However, this came to nothing. This “genuine” e-money (also known as e-token or e-purse) was only a footnote in the history of money. In almost all EU countries, credit institutions have now quietly buried this high-deficit flop. Germany is the only country where the e-purse “GeldKarte” is still kept on life support.

In the past five years, however, two other e-money versions have prevailed on the European market, where e-money is not stored on a card but on e-money accounts held by the relevant issuer on systems operating in the background:

- prepaid cards, generally with the international brands Mastercard and Visa (also known as prepaid “credit” cards), and

- closed e-money systems (such as e.g. PayPal), where credit accounts are maintained for the users, but for which no card is issued as an account access instrument (also known as software-based e-money).

e-money statistics to be used with caution

The ECB payment transaction statistics show the figures for these three product variants for the eurozone countries. However, the picture is incomplete as non-euro member states are not required to report to the ECB. This is very regrettable as, for example, the United Kingdom, unlike most non-euro countries, does not disclose this data voluntarily. As a result, we do not only lack the e-money turnover figures in the UK, but also the turnover figures regarding e-money products issued and used across borders in other EU countries by British credit institutions and the numerous e-money institutions.

Additionally, the extensive central bank statistics (86 positions on e-money!) should also be treated with great caution for other reasons. For example, data cannot be published for confidentiality reasons if they allow conclusions to be drawn about individual issuers. However, the biggest problem – despite clear guidance from the ECB – is the idiosyncratic interpretation by national central banks and those required to report. In Spain, for example, prepaid cards are simply recorded as debit cards. In Germany, too, many credit institutions do not report their prepaid Mastercards and Visas as e-money.

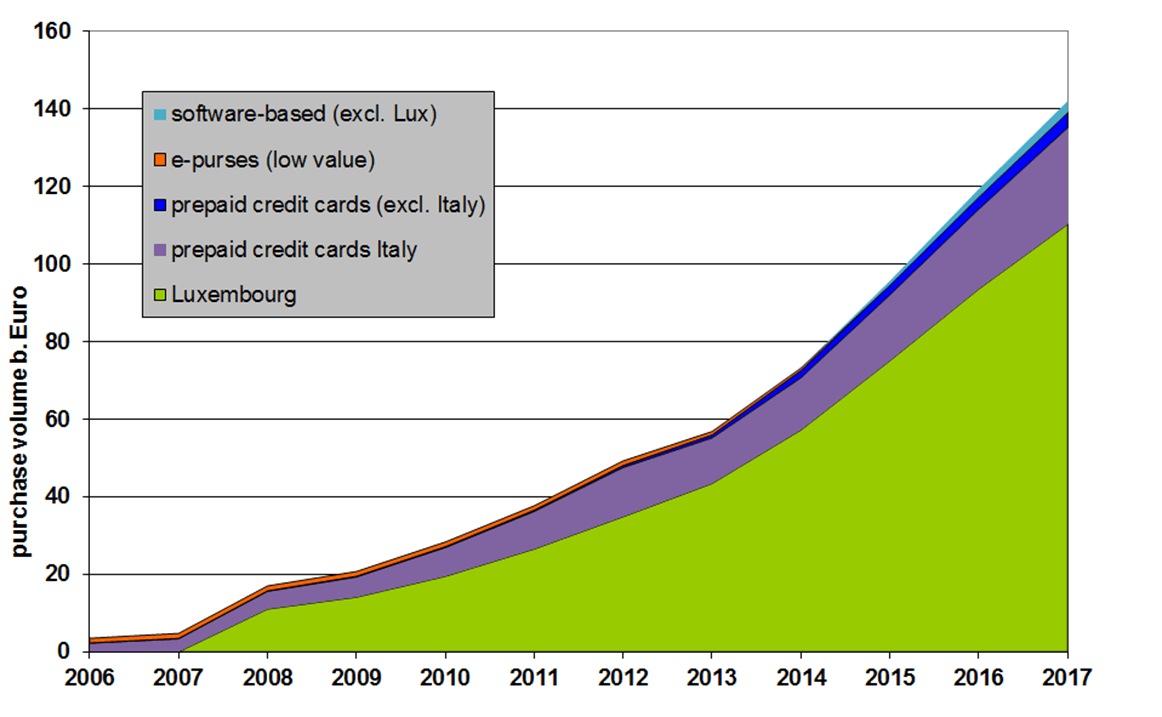

Despite these deficiencies, the ECB’s statistics provide a credible picture regarding the current trend in the euro zone. The winners are the prepaid credit cards and software-based e-money products, which accounted for a total of €142 billion in payments in 2017 (see the chart below).

Payment transactions with e-money in the euro zone // Source: ECB Statistical Data Warehouse (after adjustments in the card area)

Software-based e-money

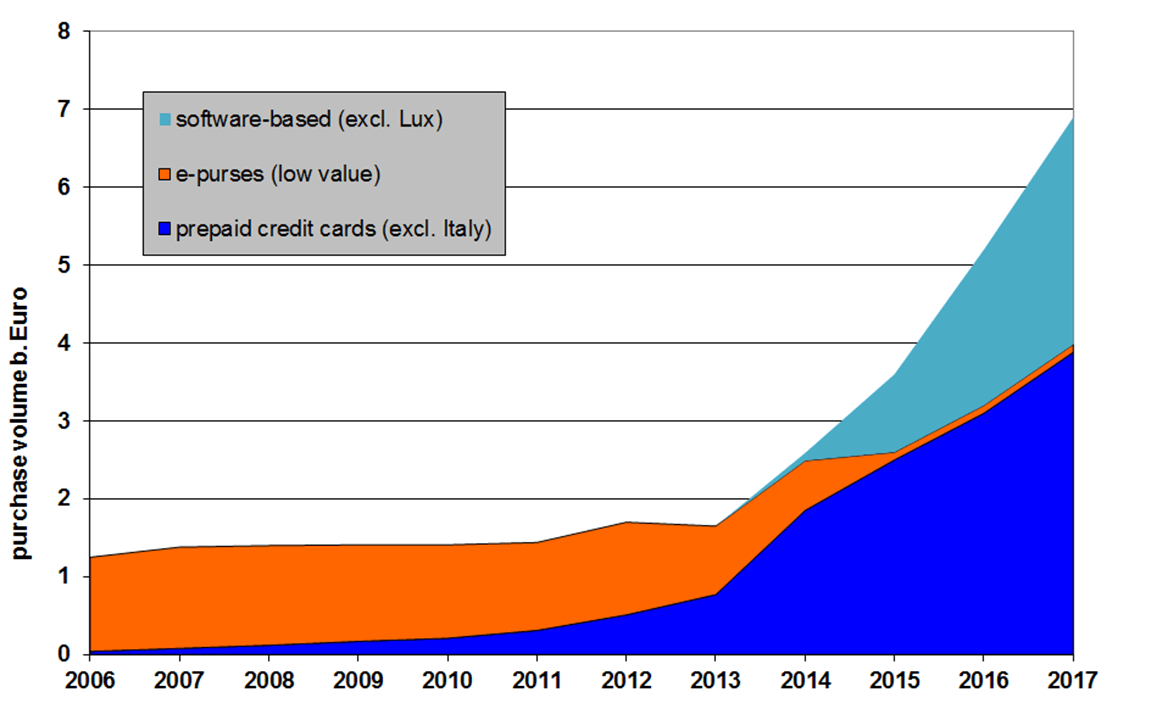

Now, approximately 90% of e-money turnover of credit institutions is generated in Italy (prepaid credit cards) and Luxembourg (mainly PayPal). If we disregard those countries, a more detailed picture transpires. Until 2013, most national e-purse schemes came to an end. From this time on, we can see strong growth of the traditional prepaid credit cards and the new software-based products.

Payment transactions with e-money in the euro zone (excl. Luxembourg and Italy) // Source: ECB Statistical Data Warehouse (after adjustments in the card area)

The numbers show an interesting phenomenon. The e-money turnover increases much more rapidly than the amount of the outstanding e-money. The figure “turnover volume / outstanding e-money” rose from 12.6 (2014) to 16.4 (2017). In other words: in 2017, e-money issuers were able to generate on average 16 times as many e-money payments for every prepaid euro. This is most likely not due to the cash management of prepaid cardholders but the “new” e-money schemes in which prepaid amounts do not remain for very long.

Amazon Pay: Where is the e-money?

A good example is a payment via Amazon Pay. The payer’s e-money account is usually empty. In case of a payment, the conventional money comes in e.g. via the funding of the payer’s credit card, is transferred into e-money, briefly makes contact with the payer’s account and then moves over to the merchant’s e-money account, who immediately has it credited back to his bank account in the form of conventional money. At the end of the day we therefore have e-money turnover without an e-money balance. This new ephemeral e-money hardly bears any resemblance to the “prepayment” as the actual DNA of e-money. This begs the question as to whether an EMI licence is required at all for such a payment system. Would it not be sufficient for merchant settlement to obtain an authorisation as a payment institution (licensed for the payment service No. 5 “acquiring of payment instruments”)? When does a clearing account become an e-money account?

Trendy ephemeral e-money

These are questions that payment transaction lawyers should answer. The current trend is likely towards quick e-money. It is likely that many of the newly established EMIs in Europe have exactly this business model in mind, such as Alipay Europe (Luxembourg), Google Payment (Lithuania) or the new car payment schemes. Both Mercedes and Volkswagen have already established an EMI in Luxembourg. The new e-money is like energy that is not stored. The cheeky question remains as to why the detour via two e-money accounts (i.e. that of the payer and the payee) is necessary at all. Why not transfer it directly from one current account to another via instant payment? That would also be ephemeral money.

Cover picture: Copyright © fotolia / rcfotostock